The ‘official end date’ of my residency at the London Cancer Hub was 31st January, and that day I held a ‘closing event’ at the ICR. Although to be honest, I will continue to work on these themes and use the learning from the residency in the immediate and the long term future, so it doesn’t really feel to me like the residency has come to an end!

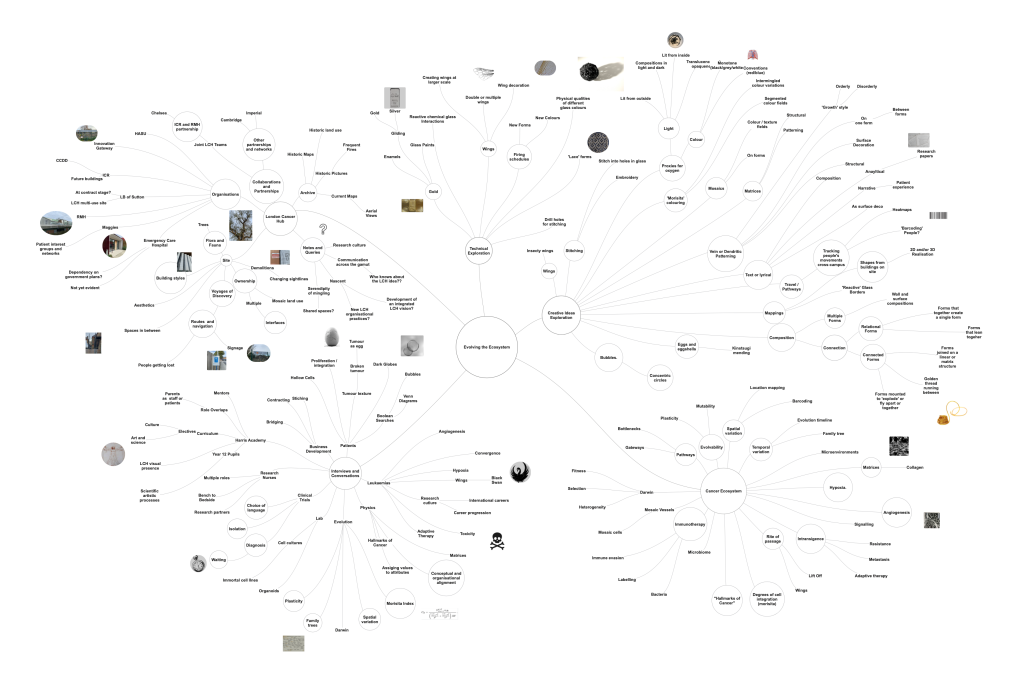

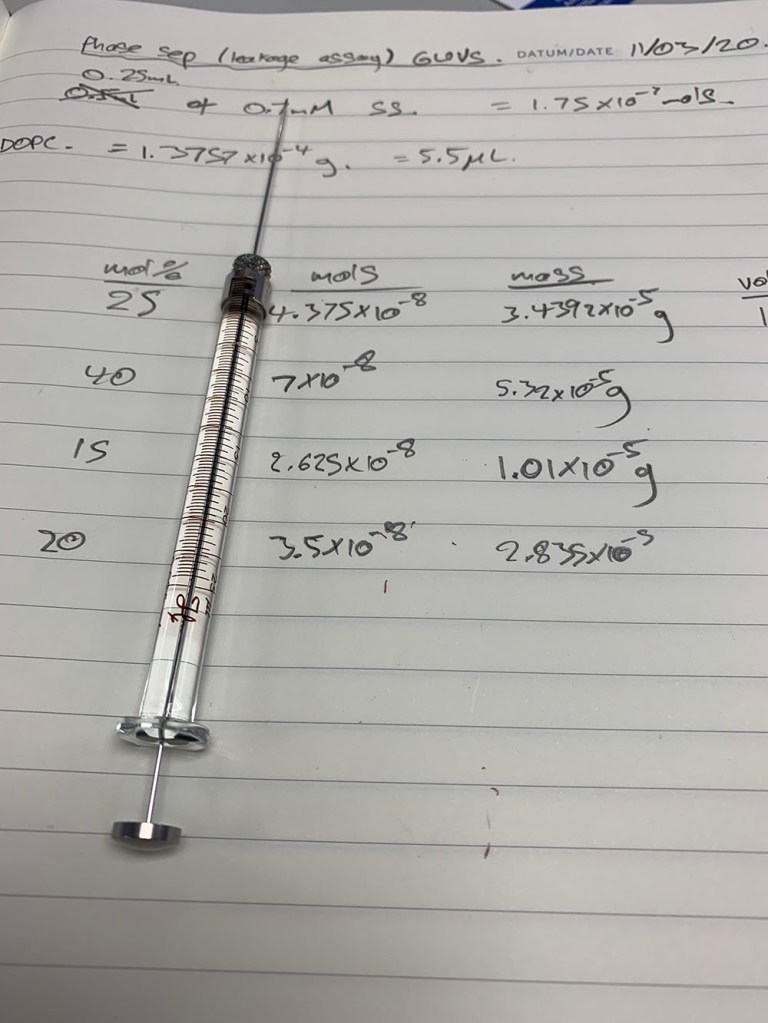

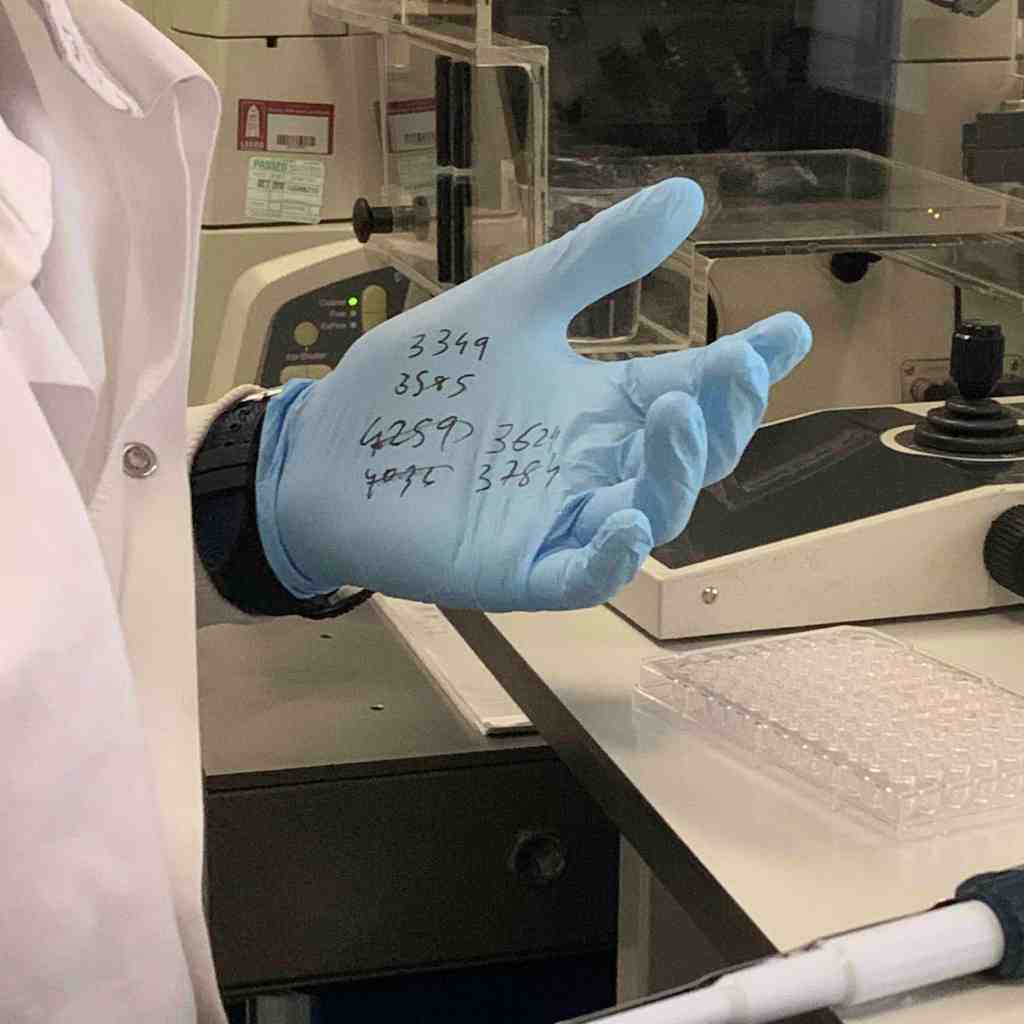

There were multiple purposes to having the event. I wanted the opportunity to share back about how the residency had progressed with those who had contributed, to let them see the tools that I had used to make sense of the experience and to show them some of the prototypes and the samples that I had created as part of the work. I also wanted to introduce others at the ICR (and potentially across the LCH) to the residency as obviously not everyone had come across me or my research. The location near the ICR reception and cafe would help with that. And finally, it would be a great chance for me to gather feedback from people seeing this work for the first time.

I was delighted that I was able to do all three things. During the course of the event, which lasted about 4 hours, around 50 people stopped to look at the work and to talk, and many more wandered by. I had surprisingly in depth conversations with about 30 people. It was really fascinating to be able to gauge and discuss people’s reaction to the work and the process. I also found out more about some research and support roles at the ICR that I hadn’t known about before.

Below I have summarised some of the things that struck me from the many conversations I had with people visiting my work.

Representational vs metaphorical vs something else?

One very interesting strand of conversation was about how far the pieces were intended directly to represent the processes of a specific element of the cancer ecosystem. I talked about how, from my perspective, I have drawn out ideas, themes and metaphors from the discussions I have had, that I have experimented with these ideas and themes in different ways, but that I am not aiming to illustrate scientific processes.

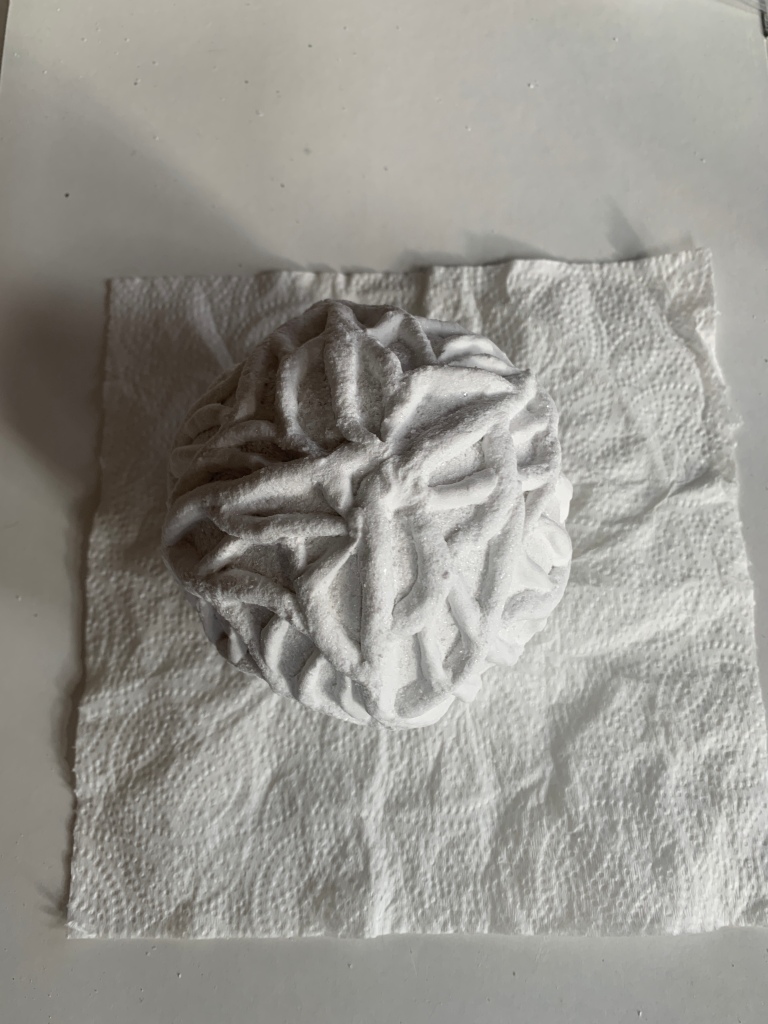

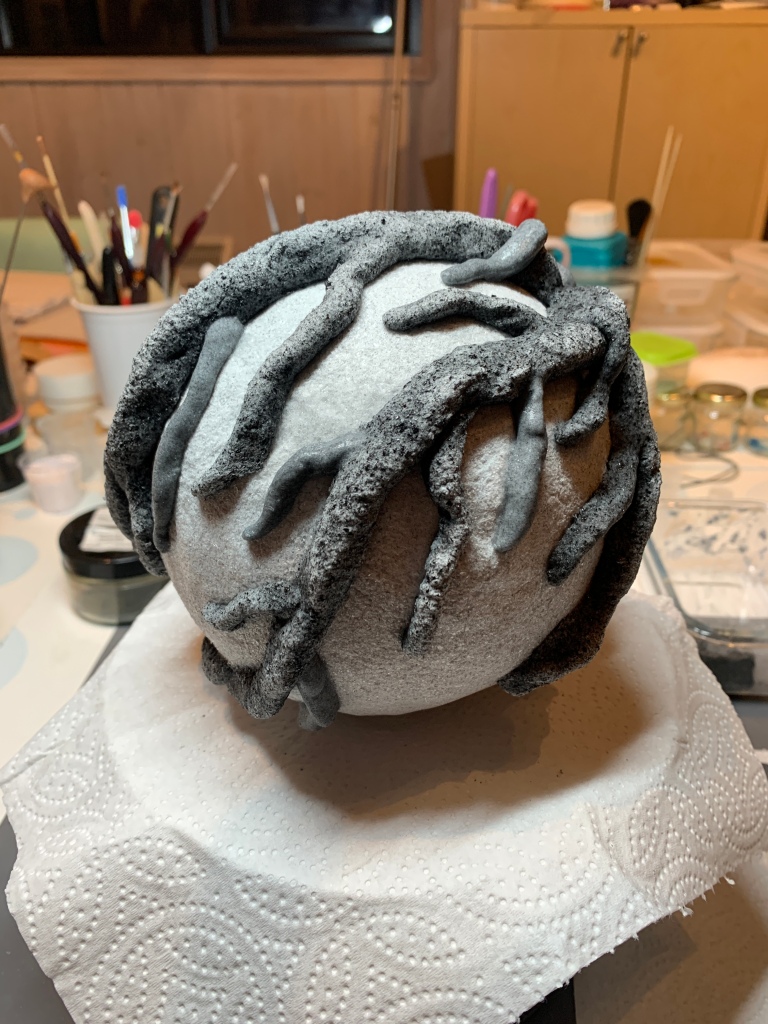

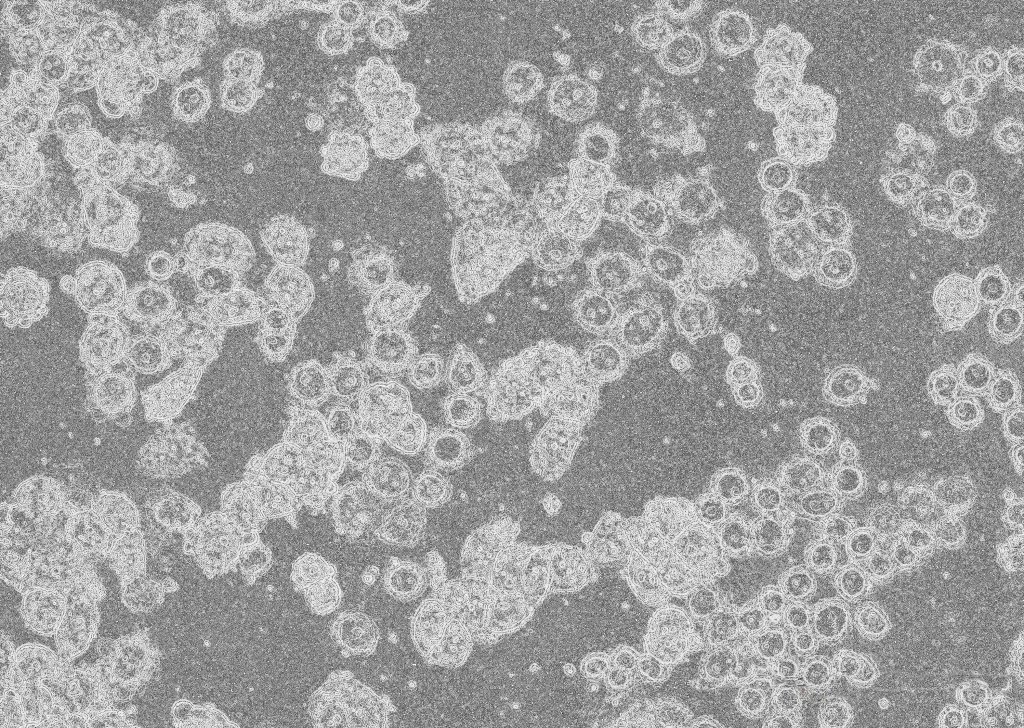

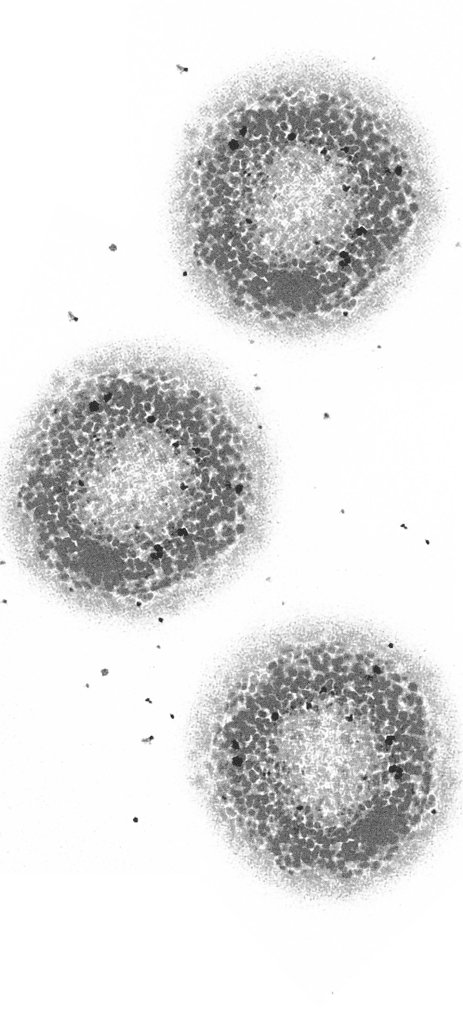

Several people asked me what the base sphere structures represented. I explained that I think of them as potentially being any of: abstracted cells, abstracted tumours or abstracted bodies. I also observed that spheres are often the starting point for my work. I ended up in an interesting conversation about how organoids look (organoids are structures grown in the lab that have some characteristics of real organs and are therefore useful as an alternative to plain medium), and concluded these pieces could also represent abstracted organoids. To me it feels quite important that they could be any of these simultaneously and are are not specifically one thing or another. I like the idea that people can take meaning from them in a way that makes most sense to them.

Another conversation about how far the work was representational centred on my choice of black for some of the dendritic patterns and the ‘cells’ themselves. I said that I had been inspired by the convention around extreme hypoxia being very dark or black. I was challenged about this in relation to the fact that the vessel growth, being on the outside of the structure, would surely be red (highly oxygenated) not black. My position was – and is – that I am not creating something literal, and that, even if i decided to do that, these samples were anyway potentially components and I was unclear at this point whether they could be inside another structure or how they would be grouped. And, of course, the structures themselves, despite the fact that I sometimes refer to them as cells, are not in any case determined (see above), and therefore it is impossible to be ‘accurate’ about a representation.

This whole conversation confirmed categorically for me that for me this work is not intended to be representational of any specific scientific process or entity and that the pieces are not designed to be illustrative or ‘correct’, Instead my aim is to draw on ideas, present them visually in different ways to stumulate thought and questioning. And whilst maybe I will convey some of my intention and thought process through the pieces, I also want to allow people to interpret the pieces according to their own experiences. I am mindful, for example, that some of my inspiration comes from patients as well as scientists, and that I have deliberately been pursuing their subjective and highly individual imaginations to inform our conversation. However, I need to keep in mind is how far the pieces – in their context of the cancer ecosystem – may be taken as if they are representational and what this might mean for how they develop and are displayed.

I was also asked about the Winged Thing and whether and how the metaphor might be explained. Would I have a caption or a label if I was exhibiting this in another context? I am to some extent undecided on that, and the context would itself be key. These pieces a) are prototypes and b) might be used as part of a composition and c) may yet change signficantly in their final incarnation, and with these factors in play, that is not a decision I can take at this point. However, I do think that if I want people to understand the metaphor specifically as mechanism of cancer then an explanation either as part of the artwork or explaining the artwork alongside would need to be a consideration.

Cultural references

I was surprised that several people referenced films when describing how they thought about some of the pieces. Star Wars and also Harry Potter’s Quidditch ball came up when talking about the Winged Thing. Spider Man and his black suit in Spider Man 3 came up in relation to the ‘tar’ overgrowth piece, particularly in connection with the idea of being gripped by something you can’t get out of.

Aesthetic and/or emotional impact

One of the things I was particularly interested in getting feedback on was whether these pieces created any emotional impact. Sometimes this came up spontaneously in conversation, and other times I raised the question of how people felt when looking at them as part of a discussion.

It seems to be having taken stock, there were a wide variety of responses. A couple of people said that they appreciated them aesthetically but did not have any particular emotional reaction. Several times people reacted to the largest dark piece and the tiny black piece by finding them ‘menacing’, or ‘threatening’, or ‘sinister’. These reactions mirrored the response I got from the Art for Social Change artists too, with whom i had previously shared some images; some people found them quite ‘shivery’ whereas others are unmoved. Very interesting.

One reaction I had was from a PhD student studying pathways in sarcoma. He said that he found one of the pale pieces much more sinister than the dark ones, as the growth around the outside was much harder to differentiate from the body of the piece – from his perspective, cancer is like that – hard to discover, hard to separate from the body, stealthy. We talked about how cancer is so much part of you, and I resolved to think about this more going forward as it chimes with my feelings about how cancer is intimately part of one’s own makeup and particular to you as an individual.

Also as part of the exhibit, I had prepared an exercise with ‘lace’ or ‘lattice’ piece. I asked people to jot down a word or two about what they thought when they looked at it, vs what they felt. Here is the outcome of some people’s contributions. An interesting mix and once again food for thought.

Colour palette

Many many of my visitors asked me why I had chosen the monochrome palette that I did for these pieces, and I explained as above that the starting point had been hypoxia. However, I got a strong feeling that people would be interested to see these or similar pieces with some colour. It set me thinking about whether I would too. Perhaps the next iteration will feature some other tones?

Two ecosystems side by side?

One of the more complicated things I ended up reflecting on as a result of the conversations I had about the project was the ‘success’ or otherwise of looking at these two ‘ecosystems’ side by side. This is something I have been wrestling with throughout the project and talked about in my research interviews also. At this event, I was challenged about whether the LCH could really be considered to be an ecosystem in any way beyond the fact that anything on earth could be considered an ecosystem. Wasn’t it just, like most things these days, an example of a network rather than an ecosystem?

On this point I would argue that the LCH in fact is more of an ecosystem than, say, a network of aeroplane routes. The LCH is an example of a social system that is developing in an environment, where different groups of people react and change as a result of their interactions with each other and their environment. Some gain useful resources, make interesting connections and thrive, others don’t. In my view this can happen both in organisational and individual levels. So from my perspective, the metaphor of an ecosystem is a useful one to understand how the LCH might function and develop, and that is a matter of importance to those who believe that bringing the London Cancer Hub together is more than a set of buildings on a site and potentially could provide opportunities to collaborate more or better with the goal of preventing and treating cancer.

At the event, I explained to people that a central question for me was to understand what could be learned from the exercise both from comparing and contrasting the ‘ecosystems’, and also as to how the two different systems might each have a place in the resulting artwork. I am coming to the position that ideas from the cancer ecosystem can be used quite successfully to interrogate the state of play with the London Cancer Hub but not necessarily vice versa. Using the ecosystem metaphor allows one to approach the idea of bringing organisations together in a system from different perspectives and ask new questions. What are the pathways, signals, and structures that are being created? Where are the areas of toxicity? How far do those work in a similar way to the biological systems? I am sure one can use these questions to help continue towards developing the LCH as a healthy, constructive and creative place to work together. However, it is much harder to see how contrasting the two systems works the other way around, using metaphors from the LCH to inform the research into the cancer ecosystem. And, to be honest, I am not sure I set out asking the relevant questions about how the LCH functions tso that one could apply the metaphors from the organisational, social and spatial environment of the LCH to see the cancer ecosystem differently. This is all part of the learning for me, and something I can set my mind to, going forward.

This event brought the formal part of my residency to an end, and in terms of this blog, it only remains to draw some of these ideas together in my next and last post on this project.