My first visit to the Institute of Cancer Research was utterly fascinating both in terms of developing an understanding of key concepts about the ecology of cancer and of getting a sense of the London Cancer Hub itself. I was lucky enough to meet with researchers from two different teams and was slightly punch drunk with ideas and information by the end of the day. Rather than write about the meetings here one by one, I plan to use this blog to think about some of the concepts and ideas and how they might translate into relevant artwork. These will unfold over future posts. This post is actually about my first visit to the site in concrete terms, how i found it, how it looked and how it felt to be there for the first time.

The LCH is near Belmont in Sutton. I was unfamiliar with my route to it by road, or the lie of the land around the LCH. I was surprised to come across the site as i was making my way through a warren of residential streets; the LCH nestles amongst the housing, mostly hidden from view.

The first buildings I saw as I came onto the LCH site (via the signposts to the ICR – there are a variety of access points) were some old brick Hospital buildings, presumably Victorian and presumably part of the Royal Marsden, past or present? The bulk of the original Royal Marsden on this site is actually midcentury, and was officially opened in 1963, but I couldn’t see much of that from my approach. I carried on past towards the ICR.

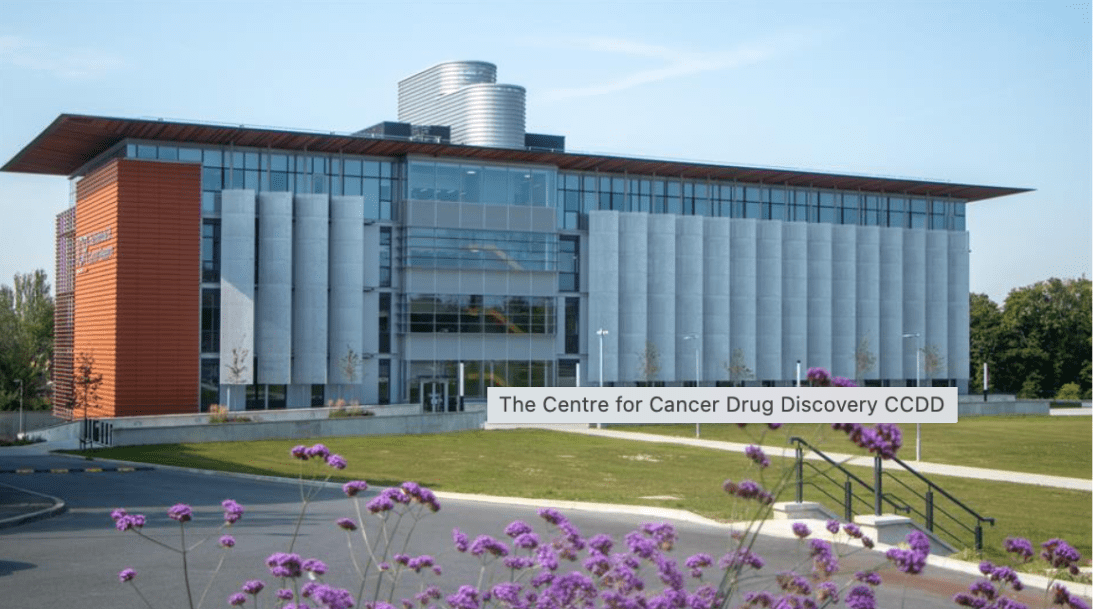

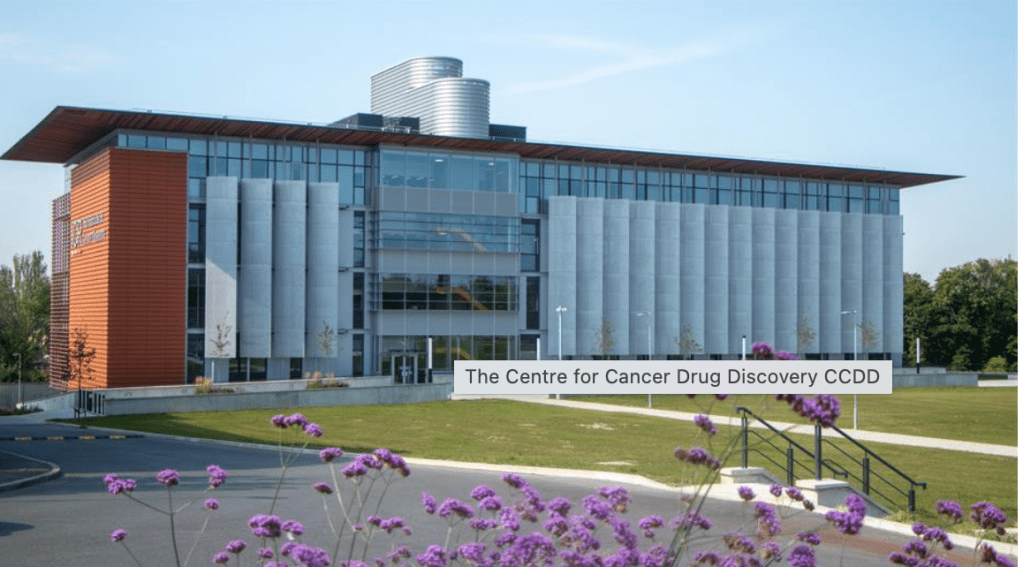

As I carried on down the access road, I came to the new ICR campus – brand spanking new buildings set in flat green parkland, some of which is earmarked for further development.

From windows of the Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery you can get something of the lie of the land. As well as being able to look over many of the different constituent parts of the Royal Marsden, it’s also possible to view the Innovation Gateway site – still very much a work in progress.

I spent pretty much all my day in the Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery where I had meetings in the purpose built meeting rooms as well as having a chance to talk to some researchers in their offices and to look at the labs used by the Cancer Evolution team.

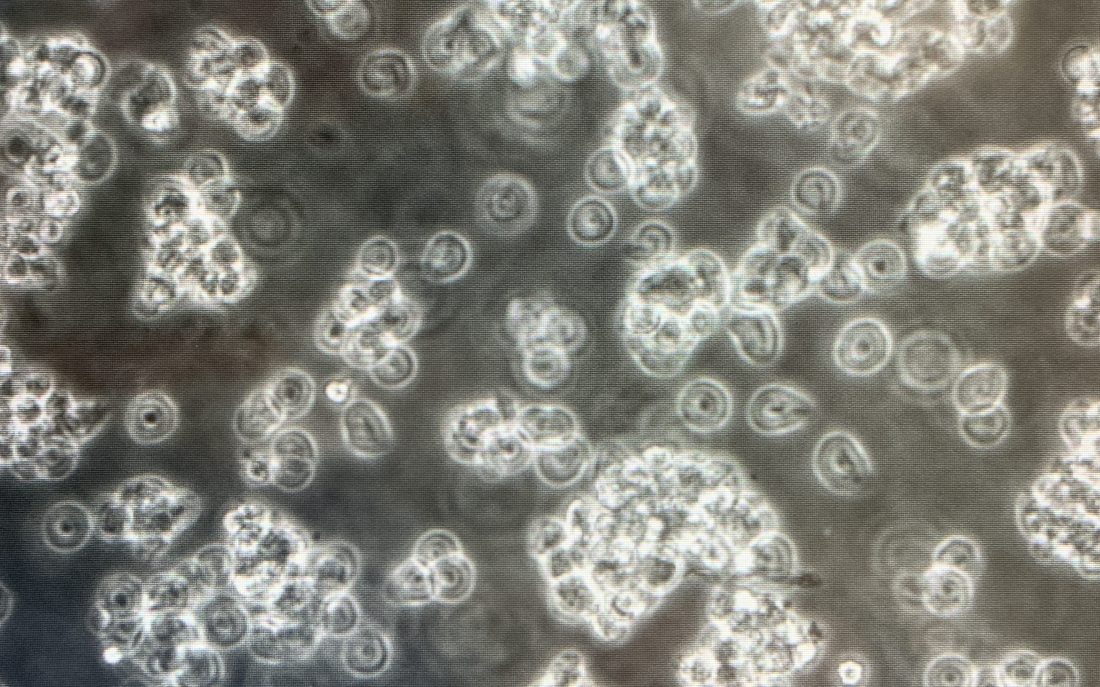

As one might expect, everything was subject to secure access – you needed a pass to get into any of the buildings, and each of the office areas and also clearly the labs required a pass to access them. I was struck by the contrast between corridors and meeting rooms, which both felt a bit stark, mainly quiet and empty, and the offices and labs which were busier both with people and with papers or equipment. In the labs I got to borrow white and blue lab coats, depending on area, to adhere to the health and safety protocols. Odd how much it felt like dressing up.

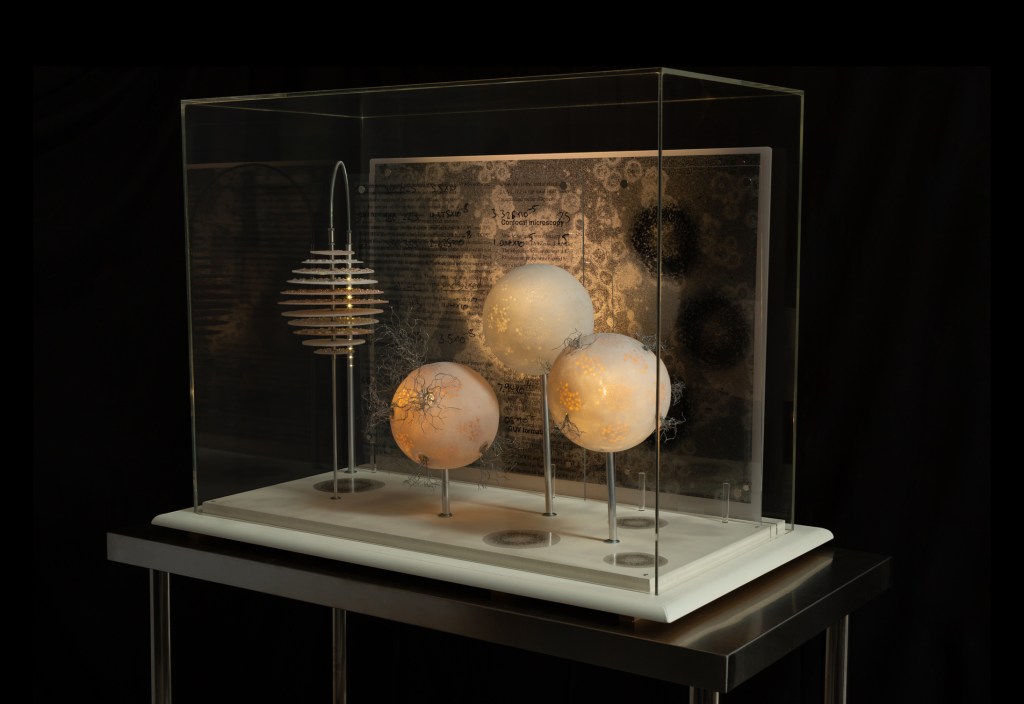

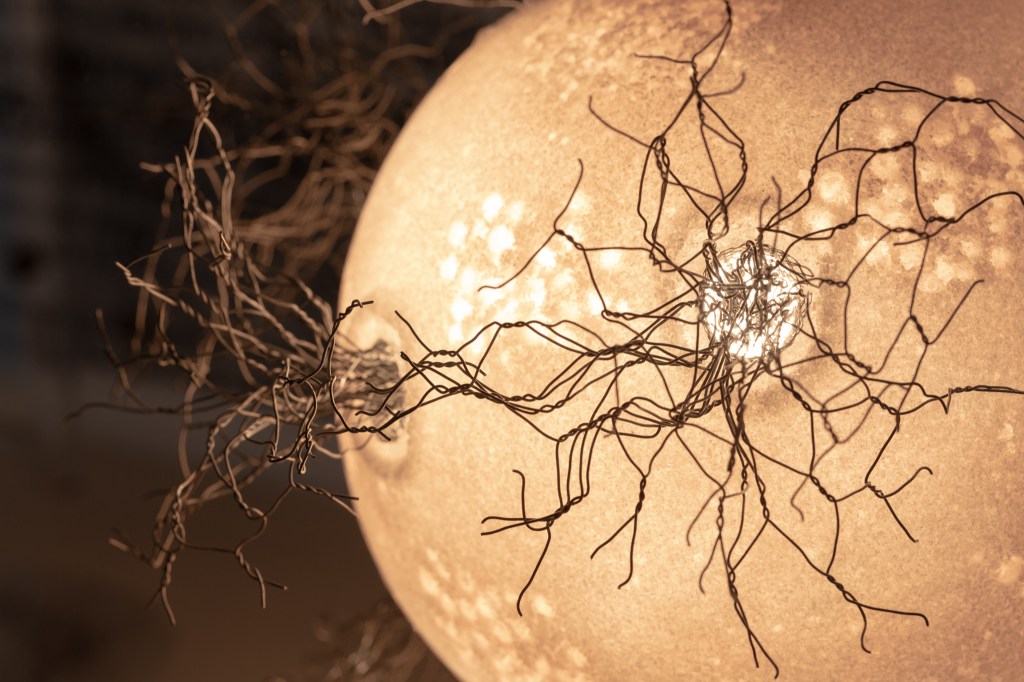

As we walked around between meetings I was trying to get my bearings (and anyone who knows me knows that’s a feat – I could get lost in a small box) but even more, I wanted to take in the feel of the place. It’s much too early to do anything here other than record very first impressions, but those impressions are very much of a work in progress, a stitching together of the very old, the very new, and all the things that came in between. It gave me a real insight as to where the project stands at the moment; the LCH is not so much an entity as an idea that is beginning to take physical shape.

And that led me to question how far the LCH is also taking organisational shape – is that totally conceptual still or is it having any impact on working practice?