As the residency closes, I have been reflecting on what I have learned and what comes next. My previous post about the closing event outlines much of my thinking at this point on many specific issues, so I am just adding a few more ideas and observations here before I conclude this chapter of Evolving the Ecosystem.

The LCH as a idea

One of the things that surprised me at the start of the residency was how much the London Cancer Hub is still an idea rather than a fully formed entity. Now that I have come through the residency I understand how true this is, and that the idea of what the LCH is – or could be – currently exists differently according to people’s roles and experiences. For some, it’s still quite a meaningless set of words; their experiences are only of a specific organisation on the Sutton site. For others, the LCH principally refers to the part of the jigsaw that is not yet built – the multi-use development site. For yet others, it’s an aspiration, and for others still, it is a nascent alliance of organisations set to get stronger. Of course it can be all of those things. The one thing it isn’t is a fully developed reality.

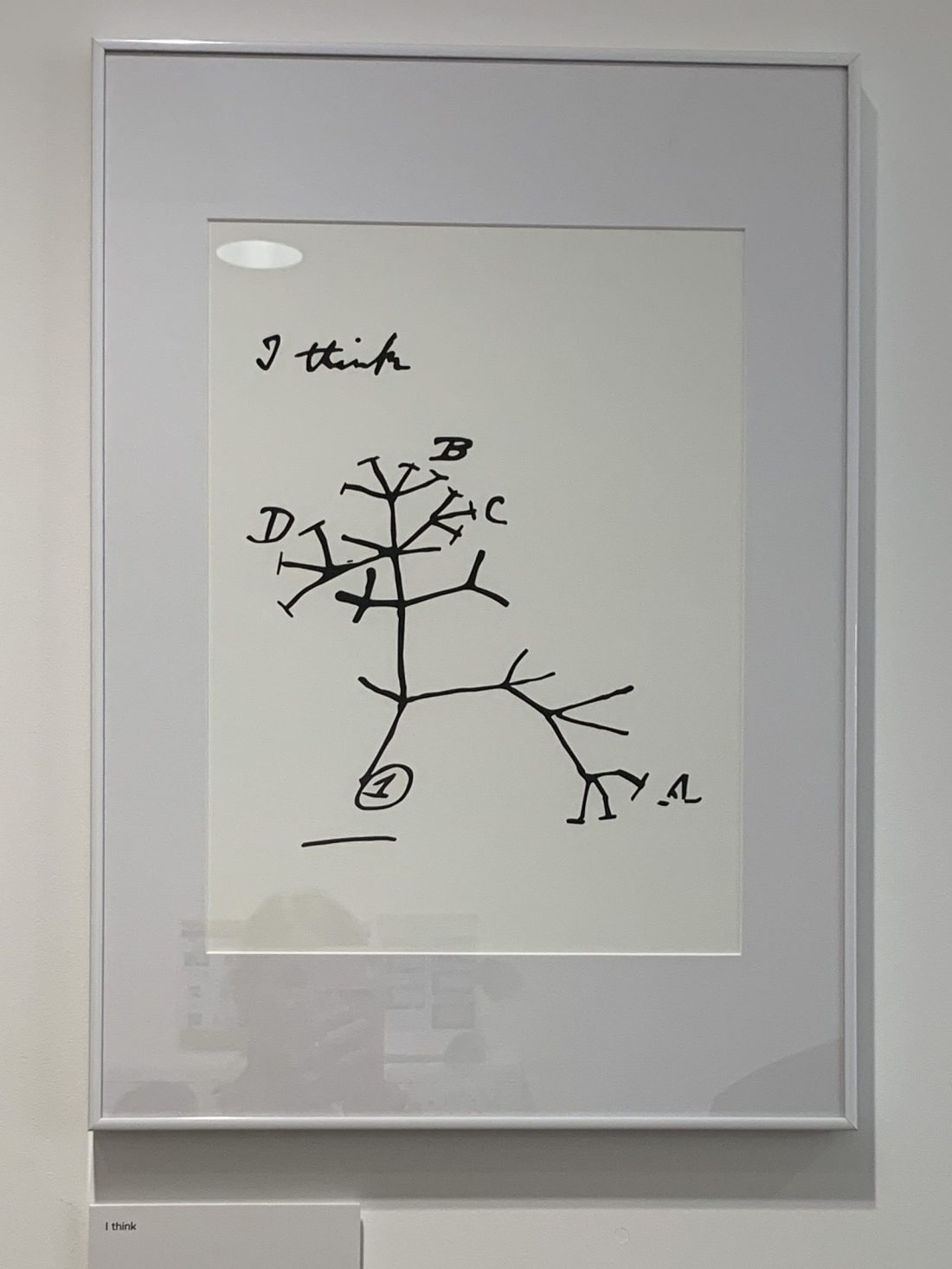

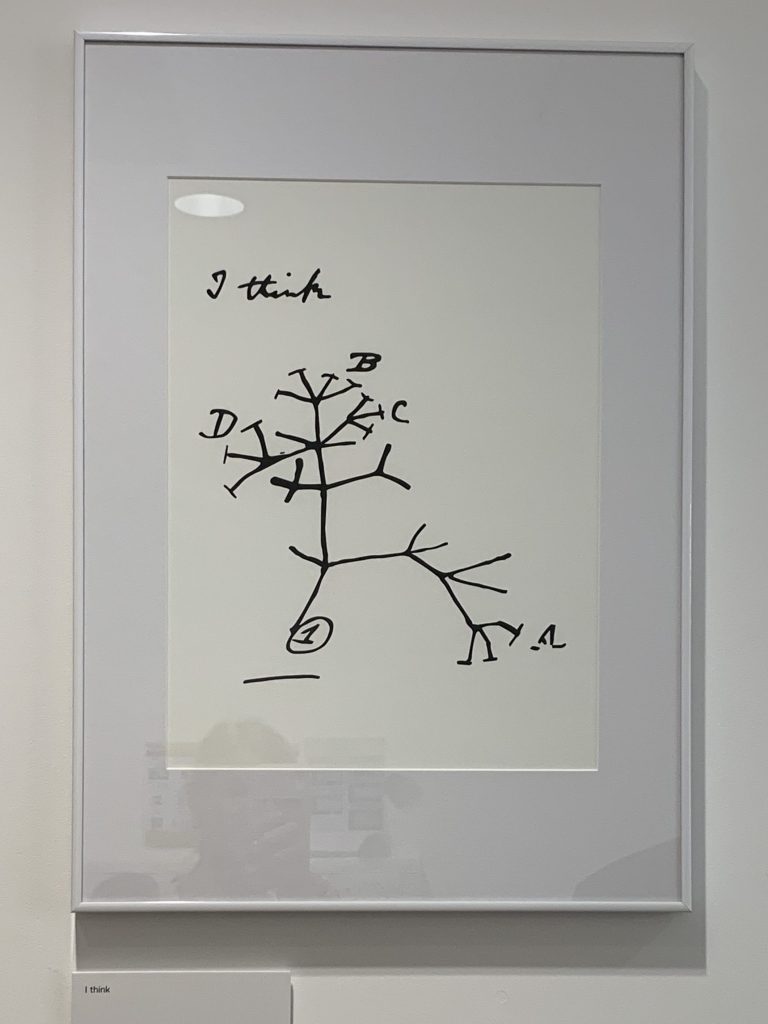

The LCH as a conceptual space

In discussing the LCH as an idea and as a location with colleagues from the Sutton STEAMs Ahead programme, we talked about the LCH not just an idea, as above, but as a space not yet fully realised, a specific place that exists only currently as a conceptual space. A lot of the work I still want to do relates to the maps and the site, and this is a very helpful construct for taking that forward, and also for understanding the potential that the LCH has to develop from concept to reality.

The LCH as an ecosystem

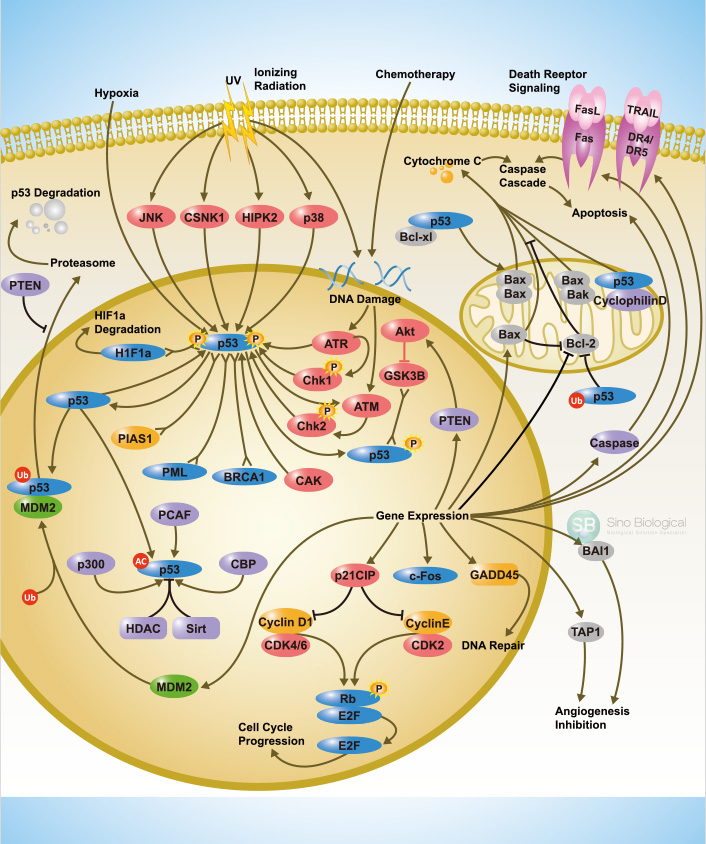

I wrote quite extensively in my last post about ecosystems and the question of whether the LCH can be considered as one. Encyclopaedia Britannica defines an ecosystem as:

Ecosystem, the complex of living organisms, their physical environment, and all their interrelationships in a particular unit of space.

To my mind there is no doubt that the LCH fulfils that definition, and that some of the metaphors from the cancer ecosystem can be applied in different ways to help us understand what’s going on there. I also think therefore that the idea of developing the eocsystem as healthy and productive and as supporting the goals of the community is a valid perspective to take, and gives us clues about some of the things that could be nurtured in order to help the LCH fulfil its potential.

To that end, I have summarised some observations about the LCH ecosystem using ideas from the discussions of cancer research. This is not an exhaustive list, and I am sure anyway that more will bubble up for me as I allow the learning of the last months to percolate. It is also not in itself ‘scientific’ though it is well grounded in conversations and observation that I have made during my residency. And finally, this is all said in the spirit of building the best possible version of the London Cancer Hub and is not intended to be critical or negative in any respect – indeed I have great admiration for all those involved in this incredible endeavour.

In that spirit, here are some of the things that have struck me most forcefully over the last few months:

Pathways: There are some well-trodden physical pathways around the LCH site and some well-trodden organisational pathways too. However, if the experience is going to be frictionless for visitors to the site, or for people to collaborate, then new pathways need to develop and existing pathways connecting people and place will need to be better signposted.

Signals: The current literal signals and signposts are patchy and mismatched across the LCH site and people get lost trying to find their way, both literally and figuratively; the signals that indicate the possibilities for more interaction across the LCH are also weak, patchy or absent in places.

Morisita: More than one individual working at the LCH mentioned to me that part of the attraction was the interdisciplinary possibilities for their work, and even pupils at the school mentioned that they were attracted by the possibilities for intermingling that the LCH offers. The Morisita index measures the degree of segregation or mixing within a population. It might be useful to understand what the ‘right’ level is on the index for the LCH or for its constituent parts and to keep tabs on how that is manifesting.

Hypoxia: Where parts of a living system are starved of oxygen, arguably, they either die or become resistant or intransigent. It is interesting what the equivalent effects might be in terms of a working culture, especially if that culture has to exist across different countries, organisations, hierarchies or departments. I have previously been involved in exploration of the cultures of research science and understand that there are risks that the culture can become toxic if no one pays attention to maintaining its health.

Angiogenesis: Perhaps a potential antidote to segregation, isolation or resource deprivation is the growth of metaphorical interconnection such as is suggested through the idea of angiogenesis. While there is no useful literal interpretation, I believe that this idea offers something slightly different from the idea of pathways or signals. Angiogenesis, when it functions in a healthy way, is all about creating connections to deliver oxygen, energy and nutrients to the entire body. Where they fail to grow, the body dies. Where they ‘overgrow’ as they do around tumours, they are an indication ill health. The LCH is currently a group of separate parts, with no full circulation that delivers to all. If the LCH is to function as a coordinated effort, some connections may yet need to develop, for example in the form of managed and/oir spontaneous communication, the sharing of ideas and energy, not only along established channels but through new ones too. And if too many channels lead to a single site, maybe that will be a way to understand that it is because not all there is well.

Do revisit some of my ‘Concepts and Metaphors‘ posts (1) – (6) if you are interested in seeing more of how I have understood the metaphors to relate across the two ecosystems.

Visualising Cancer

Having had a chance to talk to people about their experiences of cancer and how they visualise their disease as part of this project, I am increasingly aware that each person’s imagery is as individual as their cancer. Having said that, I am curious too to continue to investigate where our imaginings overlap and I hope to have the opportunities to explore how the ways we think and talk about cancer influence what we feel and see in our minds’ eye. And I also have multiple ideas for artwork stemming specifically from this strand of research that I can’t wait to develop.

Where next?

This residency has undoubtedly given me both intellectual and visual inspiration that will last me for a long time, but you have to start somewhere. I have identified two projects that I want to make a start on soon after finishing this residency. The first is to use the ideas from my prototypes to create a site specific sculptural installation. I will start looking for a site immediately as I want to be able to use a specific location as a canvas for creating the piece. Secondly I intend to start to develop and perfect some pieces responding to the broken egg and other ‘visualising cancer’ themes. I am looking at including textual elements as well as visible mending and am as enthusiastic to get started with this as with the previous idea.

I’m going to be busy!