Today’s ideas are all about routes, travelling, and journeying. Some seem to be so commonplace that they are not really thought about as metaphors at all. And I’m also beginning to pick out metaphors that are more clearly ‘metaphorical’ and used deliberately because of their non-scientific connotations.

Concepts in a cancer context

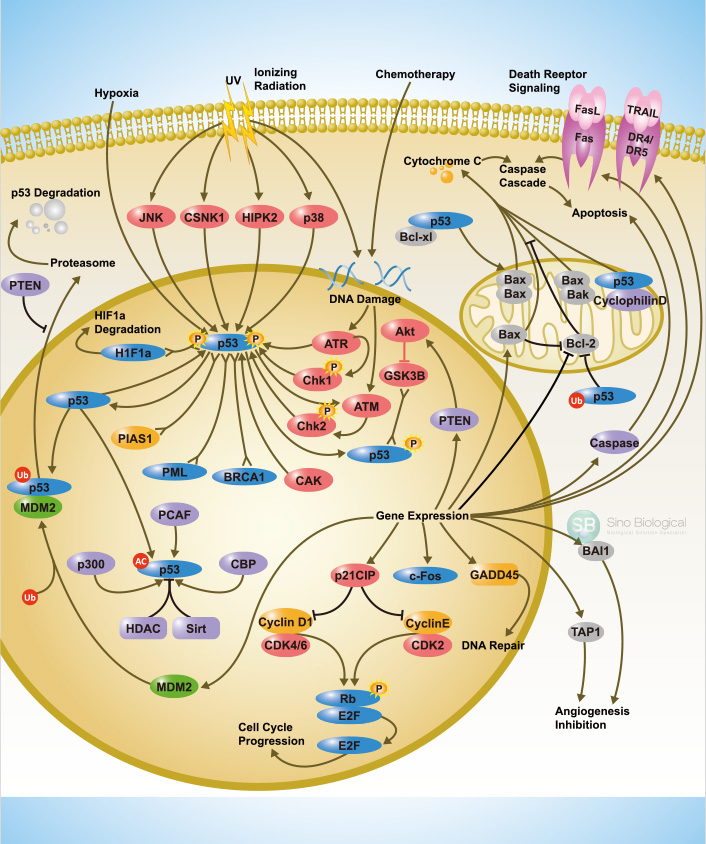

Many of my descriptions about how these relate to cancer are drawn from a fascinating conversation with the Biology of Childhood Leukaemia team in a discussion about the role of gene TP53 in regulating cancer and the effects of hypoxia (lack of oxygen) on cancer evolution.

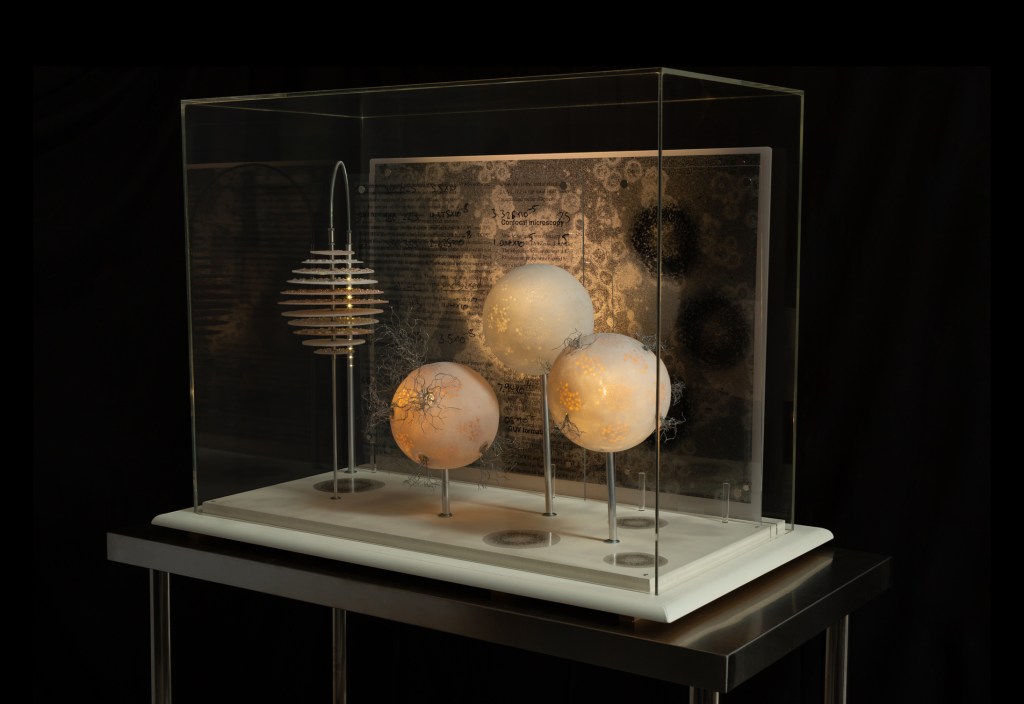

“Pathways”

Steps in the process that govern a cellular system. For example, the TP53 pathway is the one that a cell goes through in terms of whether it is ‘allowed’ to replicate, is sent to be fixed or if it is earmarked to die.

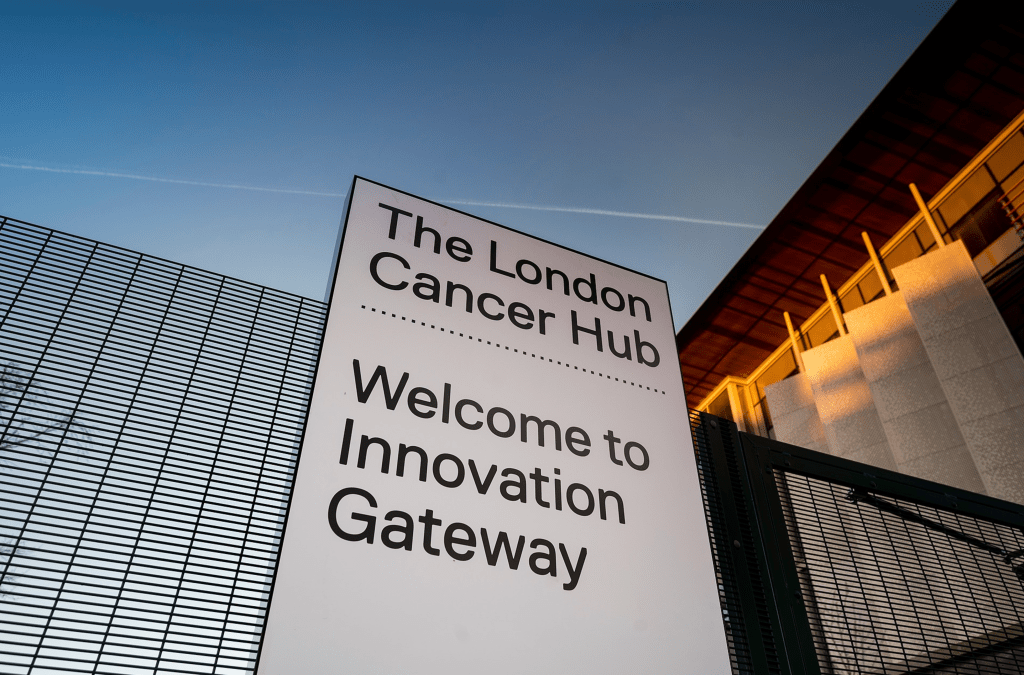

“Gateway”

On a pathway there can be a gateway, such as the gateway that cells go through on the TP53 pathway, for example, in order to know if they should go forward to replicate or stop and die. This is a gateway that can become very ineffective in cancer – cancer cells do not die in the same way as normal cells – and may be related to changes or mutations of the TP53 gene.

“Bottleneck”

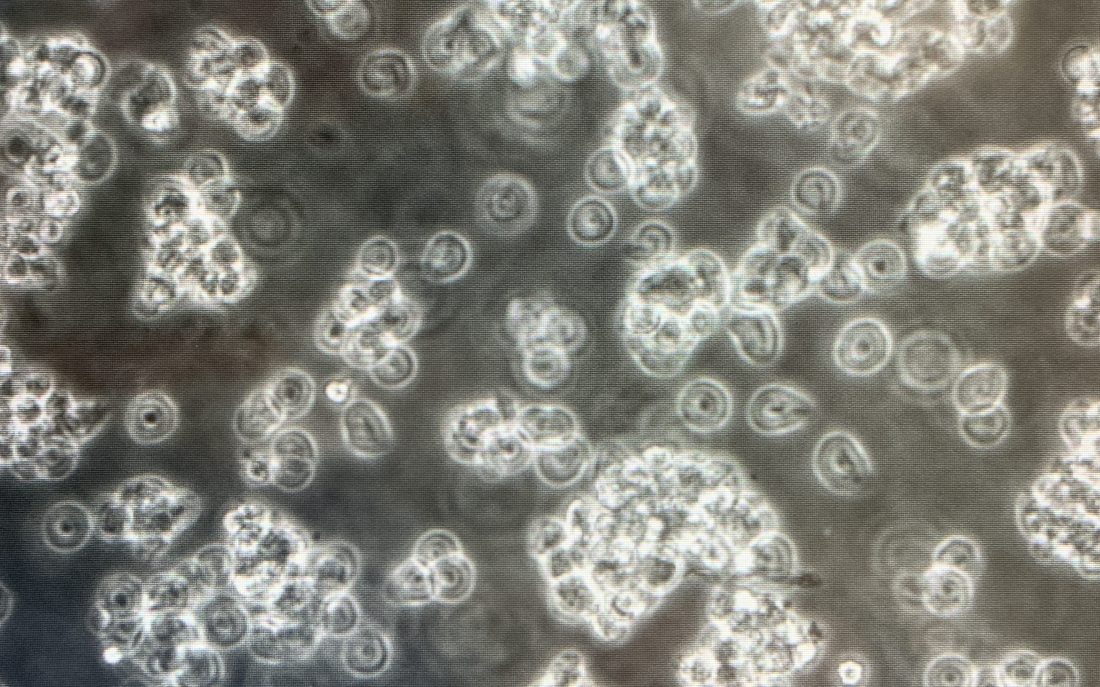

A point at which many cells fail and a few pass through such as in the toxic environment at the centre of a tumour where the majority of cells die but one or two may replicate with mutations that allow them to survive.

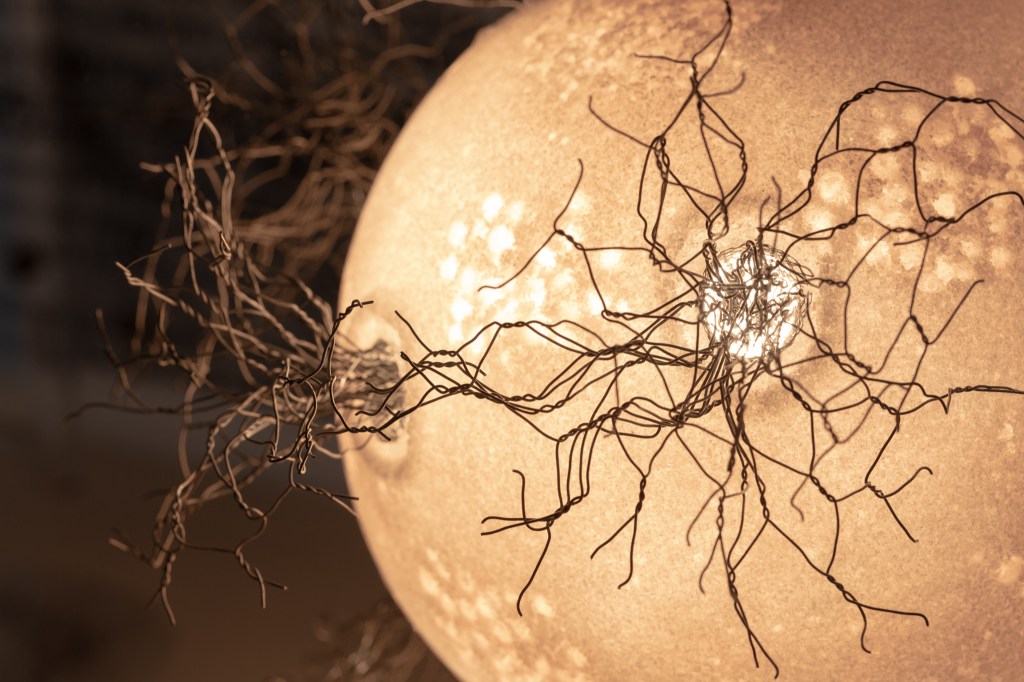

“Signalling”

How cancer cells communicate with surrounding cells. Eg, they can signal to the body to grow more blood vessels to a tumour. Signals can be proximal (ie next door with surface proteins) or longer range chemical (eg with hormones etc).

“Rite of Passage”

This is a more specific metaphor drawn from one of the papers of the Childhood Leukemias Team. This metaphor represents the point of no return in cancer. Specifically, the ‘rite of passage’ in the paper refers to the the point at which the TP53 mutation allows cells to transition through EMT and launch themselves into the rest of the body. THis is the point where cancer metastasises, after which the hopes of ‘cure’ are drastically diminished. A rite of passage indeed.

How all this relates to the London Cancer Hub

While talking to ICR researchers the idea of spatial movement came up frequently, both in terms of their research and about their personal movements around the site and around London. While it seemed to me that in terms of the site, they concentrated on the ICR part of the campus, several mentioned how walking past or through hospital buildings either as part of their journey to work, or to collect samples or meet with clinicians, reminded them of the ultimate purposes of their work. This was especially true when they cam into direct contact with patients, even if this was just seeing or passing them on their own pathways,

Movement around the LCH was not the only example of establishing pathways in a very literal sense. Several researchers also told me about their regularly trodden routes around London as part of their work. For example, one scientist talked about how at one stage in her work she was travelling frequently – occasionally daily – on a circuit between the Sutton ICR, the Chelsea ICR and the Imperial College campus at White City. Interestingly, her work was heavily focused on identifying the spatial arrangements of different cell types in tumours, which are ‘barcoded’ to keep track of their position. We chatted about the possibilities of tracking the movements of researchers in a similar way. I would love to track some staff across the site and see what visual mappings came out of the exercise. I’ll be posting more about the site, its history and pathways through it in a forthcoming post…

And the ‘rite of passage’ for the LCH? I could interpret that in so many ways, so I am going to hold back and see what else emerges,